In 1934 Stefan Zweig in a biography said Erasmus represented the supranational ideal He used the term ‘supranational‘ many times throughout the book. What did he mean?

Robert Schuman declared on 9 May 1950 that peace could be built in Europe based on the same supranational principle. It brought an end to 2000 years of Western Europe’s internal wars.

Look back over the last 500 years since the great work of Erasmus in

1516 in publishing the New Testament and exposing the fraud of priests and the Vulgate version of the NT. What do we see? We witness a world changed from top to bottom. Science and

technology are the great dominant forces in society. That is based on the axiom of a Creator God who brought laws of physics and mathematics. That central concept did not come from pagan superstitions of Rome and Greece. We owe much of our

comfort and prosperity and the fecundity of earth’s population to

science and technology. So it would seem.

The elements, the materials and the means to assemble the

proponent parts of inventions existed throughout the history of mankind.

Are we more intelligent today? Probably not, probably the reverse. Many

of our everyday books on mathematics, philosophy, and politics

originated one, two three millennia ago. How many people today could

write from first principles a book on the geometry of conics or work out

how to predict eclipses like the ancient Babylonians did?

Why is it then that only our last half-millennium was able to put the

various pieces of these many different jig-saw pieces together to

create a jet plane, satellite technology or a probe to the limits of the

solar system and beyond? What sparked our scientific and technological

revolution from around 1500? Up till then society plodded along at the

same speed as the Romans and ancient Greeks.

We have electricity – a force that propels much of our traffic. It

sparks our internal combustion engines. It propels our electric cars,

some of which now drive themselves without the aid of a human.

Electricity activates tiny splodges of metal on boards made from the

same silicon material as seaside sand. We call them our computers. It

also makes our light for us to see at night. It powers our ability to

communicate as

I am doing right now. Artificial intelligence answers our

verbal questions.

What lies behind this great change of society, this supranational

innovation that changes the way we live and think? Was it the genius of

one man? Do we owe all this to someone like the practical Michael

Faraday or the mathematics of James Clerk Maxwell?

Here we are confounded by the facts of history. Our west European

society was not the first to have electricity. We may have been the

first to exploit it on such a wide scale.

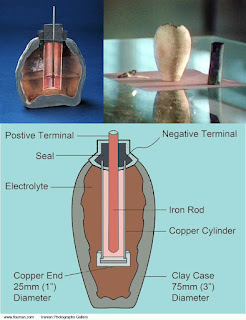

Two thousand years ago, the Parthians, that great super-power that rivalled and defeated the Roman Empire many times, possessed the electric cell. The construction of it implied that they used the cells in series to create a stronger current of electricity. They may have used the electricity to electroplate base metals with gold or for other uses we know not of.

But they did not, as far as we know, create semi-conductors as the essential elements for digital computers.

Some intellectual impulse far greater than the life-and-death

battles, that the Romans fought on the Euphrates, in Israel and Greece,

ignited and motivated our western society. The Parthians had abundant

wealth, wealth so great that it provoked the covetous Romans to try

vainly to conquer them.

The Parthians also debunk a common assumption of today’s Erasmus programme

of student exchanges. The presumption is that students will gain from

cultural exchange. Science will progress because one set of students or

scholars interact with another who approach a problem from a different

cultural point of view.

Yet the Parthians had global reach in their cultural interactions. They traded with the Far East. It was probably the Parthians who in the first century introduced silk from the Far East to the Romans in their Far West.

Mixing cultures may have some positive results. What is more important is to let truth flourish and not smother it with myth and nonsense. That weakens truth.

Despite all this cultural exchange neither Romans or Parthians

had aeroplanes. The native brilliance of Parthian rulers established a

rich and long-lived empire that confederated different tribes and

competing religions for nearly 500 years from 250 BCE to 226 CE. Neither

Romans or Parthians produced a scientific society like our own. Why?

The Romans on the contrary may have destroyed the early roots of it.

One can perhaps excuse the Roman Empire for its lack of

accomplishments in these areas. It was for most of its time involved in a

bloody struggle to attain the peak of a military dictatorship. Once

they had reached the emperorship, many of the emperors gave themselves

over to sexual excess and the persecution of dissenters.

What of the great engineering accomplishments of the Roman Empire?

These have been much vaunted by too many of the West’s historians who

still live under the Stockholm symptoms of the Roman conquest of their

lands. Many of the most extraordinary achievements of the so-called

Roman Empire were in fact due to engineering skills that existed prior

to Roman conquest.

Take for instance, the building of a harbor at Israel’s

Caesarea, from nothing. It became the largest port in the Roman world. Jewish engineers

set huge limestone blocks 15m by 2.7m by 3m exactly in place, one

exactly on top of the other, in 60m depth of seawater. Figure that out.

Then look at the great fort of Jerusalem, Antonia. How would you manoeuvre a polished limestone oblong block

13.6m x 3m x3.3m still in its foundations? How would today’s engineers,

smooth it to perfection and place it exactly within millimeters? It

weighs an estimated 570 tons.

Look high to the mountain fortress of Masada where a city and a palace with its Roman baths were created in what many would today say was barren, arid Dead Sea.

In the west Keltic Britons built hundreds of astronomical circles and

ellipses to measure the calendar and examine the stars. Hero of

Alexandria, Egypt, created a steam engine but neither he nor the next

generation built a locomotive.

The Antikythera Mechanism was a fished out from a vessel sunk off the Greek island. It contained an amazing array of cogs and delicate settings. What was its purpose? It was a mechanical computer able to predict the movement of the planets, eclipses and dates based on the 19-year Metonic cycle that controls our seasons and religious festivals. This Metonic cycle is the basis for both Judaism and Nazarene Christian worship. At the center is that axiom that the sun, moon and planets were placed there as our time-keepers by the Creator who set the laws in motion.

Our last 500 years has not just seen great engineering achievements

and computers, it has seen together with the microscope the realization

that human beings are composed of cells. Further, for the proper

functioning of the human body, we call on 100 trillions of bacteria and

other creatures. Each human is really a community of living organisms.

Scientists have explored the material components of the cell such as

its DNA and the part it plays in genetics.

Why did ancient societies not investigate these vital matters themselves? Were the microscope or the telescope too complex for a society that could create the Antikythera mechanism around 100 BCE? Not at all. Did the microscope require the intervention of a highly educated scientist and advanced optics?

A century-and-a-half after Erasmus, the Royal Society in London was amazed at the extraordinary sketches of microscopic creatures coming from a correspondent, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, in the Netherlands. From 1670s he wrote more than 500 letters to the Royal Society about his discoveries. This self-educated, independent-minded businessman invented a single-lens microscope that could render visible unicellular bacteria, sperm, blood, and minute water life.

The Royal Society was set up by convinced Christians who held that we live in a world of physical, mathematical and moral laws. They rejected the dogmatism of untested experts. They wanted experimental proof.

Today we know that the human body is composed of nearly 100 trillion cells, with more than half independent uni-cellular bacteria

etc. This form of life makes up most of what we are, not our own flesh! With specimens

attached to the spike he could examine the various types of life on

this planet — some of these forms were eternal — and they did not need

sex to reproduce.

Yet Leeuvenhoek, “the father of microbiology” created his single lens from a small sphere of glass. And glass has been around for 4 or 5000 years. It was a recognized profession and trade. Ancient Egyptians made multi-colour glass vessels that compete with the finest Venetian glassware. Where were the ancient Leeuvenhoeks in antiquity who looked through a tiny ball of glass? Why don’t we have an Egyptian name for the father of microbiology?

From around 1500 all areas of knowledge, science and technology

flourished all across Europe. What was the motor? Did Erasmus know it in

1516? What was the secret that Erasmus spoke of, when in 1517 — 500

years ago, he wrote:

” At the present moment I could almost wish to be young again for no other reason but this — that I anticipate the near approach of a golden age.”